History of French Tapestry

11th Century

Although the weaving of tapestry has been dated back to the ancient Egyptians, we start herein the origins of French tapestry dating from the 11th Century

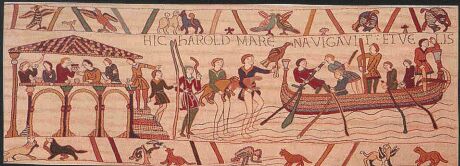

The Bayeux Tapestry is the only masterpiece of it’s kind in the world and is a historical record retracing the events leading to the conquest of England, and culminating with the Battle of Hastings in 1066 by William the Conqueror.

The story of the tapestry begins in 1064. The tapestry is in reality a hand embroidery on linen cloth using wools of various colours. The tapestry is 70 metres long and 1/2 metre high, and was most probably woven in an Anglo-Saxon workshop supervised by Odeon de Conteville, Bishop of Bayeux and half brother of William the Conqueror.

12th Century

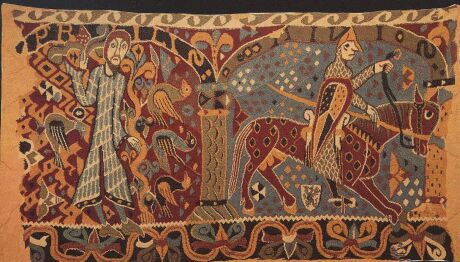

The subject matter of tapestries from this period is characterized by extreme awkwardness of design, proportion, perpective and detail. The designs translated into the medium of tapestry from this period appear quite primitive and childlike, especially when compared to the masterpieces of the 16th-18th Centuries.

Les Mois de’Lannee (depicted above) is a surviving fragment of a late 12th Century tapestry from Baldishol Church in Norway and is a wonderful example of awkwardness of transposition of 12th Century design into the medium of tapesty and is one of the oldest surviving tapestries in the western world.

The two scenes in the fragment represent two months of the year – April, which is legible on the top left and is symbolised by a man holding a hflower next to a tree upon which two birds are climbing. The month of May was the “warring” month and is depicted by a horseman wearing a helmet, coat of chain mail and carrying a lance and shield.

13th Century

The use of tapestries at this time was more for practicality than that of artistic, decorative or comemorative value. Kings and Lords traveling from one castle to another were fond of tapestries, for when rolled up they could carried and hung on the walls of various residences for protection from the cold and noise in the large rooms, most of which were damp and noisy as the windows were without glass and the floors were paved with flagstone.

Canopy beds originated from the custom whereby tapestries would form small comfortable areas within a room amidst the coldness of stone and in which it was possible to sleep in warmth. When a guest would arrive, usually in a common hall, the Lord’s room was immediatley “dressed”: a canopy for his bed was arranged and cross-walls of tapestry placed north or south to protect against cold in winter or warmth in summer.

When the Lord’s moved into a new castle they would not hesitate to have a tapestry cut so as to facilitate a door opening. Whenever the ceiling of a room was too low to hang the tapestry at full length, the bottom of the tapestry would be cut-off, which was kept and then sewn onto another tapestry found too small – even if the theme and colours were different.

Such 13th Century tapestries, a small number which survive today still continue to puzzle historians.

14th Century

Up until the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), France was the most important producer of tapestries and Paris was the undisputed capital. Tapestry design had evolved from the extreme awkwardness of the 12th Century, however movement, proportion, perspective and composition were still cumbersome and the tapestries were composed of improbable associations of the subject matter.

The tapestry above – Bataille et Embarquement (of unknown origin), depicts a combat that is most likely drawn for the Iliad, and shows Knights, archers and mercenaries in battle with a galleon in the background that is reproduced in such a amnner as to appear on land. In the foreground, Royal people are depicted with composed dispositions amid a chaotic battle scene. The tapestry is on display in the Cluny Museum, Paris.

Late 14th Century

The 100 Years War and the systematic plundering of Paris sent the tapestry makers fleeing northwards to Arras (Ateliers d’Arras), where they set-up their tapestry studios.

The tapestry depicted left, Offrande du Coer, is attributed to the Arras workshops 1400-1410 and is currently at the Cluny Museum in Paris. This tapestry depicts a finely dressed young man offering his heart to his favourite – a tapestry expressing an atmosphere of tenderness and affection.

15th Century

Towards the end of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the pillaging of Arras in 1446 by Louis XI sent the tapestry manufacturers towards Flanders which became the tapestry centre.

The tapestry craftsmen, working in family concerns whose manufactuing skills were passed down from father to son, had to possess skills not only of weavers but also of dyers, the two skils being interrelated, and a knowledge of which was necessary in order to bring a successful conclusion to the tapestry. Their secret lay in the skillfulness in extracting colours from various plants and incorporating them into the wool. This method gave them a palette of only 12 colours from which to work (modern computer screens have 16 million colours).

Materials used in the weaving of the tapestries were Arras thread, (aka Picardy wool), Italian silk, and silver and gold threads from Cyprus. Tapestry manufacture was slow, taking a skilled worker about two months to weave a square foot (approx. 30 cm square).

Many large tapestries were a group effort, each worker having his own particular portion of the tapestry to weave which would be joined at a later date. This lead to the weave having different tensions and techniques within the one tapestry – some portions of the tapestry more taught than others.

The tapestry makers wove biblical scenes and at a later date, scenes from mythology; taking their inspiration from the translations of Greek and Latin texts. The lives of saints were widley represented and the background was either a temple, palace or simply a solid colour. The costumes were seldom of the era depicted in the scene, more often borrowed from colourful biblical illustrations.

These picturesque anachronisms gave a particular charm to the tapestries of the 15th Century, also known as Gothic tapestries and later as Flemish Gothic tapestries. The composition of the tapetries depicted an awkwardness in perspective and landscape backgrounds. It was to be the next century before the genius of a Raphael was to bring tapestry to the true art of composition.

The purchaser of the tapestry usually dictated the subject, size, number of pieces, themes, subject manner and attitudes. Working in close collaboration with the tapestry worker was a a painter who created the preliminary designs or paintings, within the restriction of the palette of colours of the threads available to the tapestry weavers.

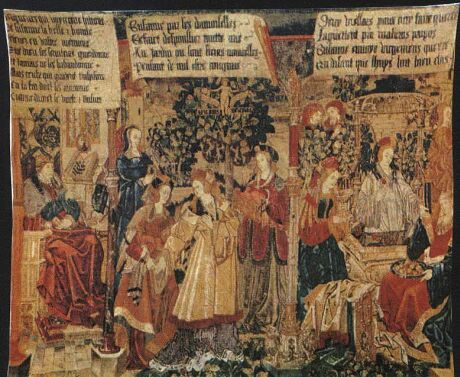

The tapestry above Suzanne et les Viellards (Marmattan Museum, Paris) is a fine example of a biblical scene. All the vitality of this work lies in the expression of the faces. Clothes make up a superb symphony in which reds, blues and golds are blended in the purest Gothic style.

Mid 15th Century

Towards the end of the 15th Century, continuing into the 16th Century, the Loire Valley (Southeast France) became a popular place for tapestry makers as it was the favoured area of the French Aristocracy for their country retreats. Rural scenes with freshness and charm, where gentle ladies, lords and peasant folk are depicted on a flowery or “mille fleur” (thousand flower) background of the Loire Valley.

The garments of the people depicted in the tapesries were seldom in accord with history and time, often imitating the court garments that were fashionable at the time. The subjects were adorned with gold and their garments were trimmed with exquisite fabrics and furs, even the peasants appear like aristocracy. As most documnets concerning tapestries of the 14th-16th centuries no longer exist, experts generally refer to the costumes of the subjects to establish the date of execution.

Le Berger tapestry (above left), is an interesting tapestry because two components of its content are influenced by the style of two periods from the 15th century. The captions at the top and the right of the tapestry are of the early 15th Century Flemish Gothic style and the flowers at the shepherd’s feet are of the style “mille fleur” (mid 15th – early 16th century).

La Danse tapestry (above right) is part of the famous set of the “Noble Pastorale” series of tapestries created around the mid 15th century and is characteristic of the tapestries made by the manufacturers of the Loire Valley. The background is entirely Mille Fleur.

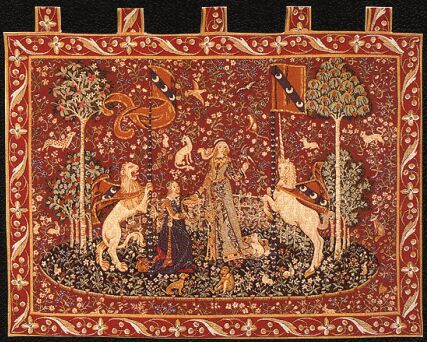

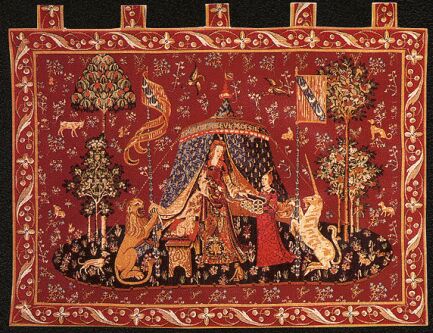

The tapestries Le Gout (“taste” – below left) and A Mon Seul Desir (“my only desire” – below right) are two tapestries from within the famous set of six Lady and the Unicorn tapestries on display in a purpose buit room within the Cluny Museum in Paris.

Five tapestries depict the senses of taste, sound, sight, smell and touch and the 6th tapestry, A Mon Seul Desir (above right) representing an allegory, the meaning of which has been debated by historians for centuries. Scholared opinion today believe that the tapestry depicts a young lady returning a necklace to a casket, held open by her maidservant. The inscription on the tent “A Mon Seul Desir”, coupled with the ladies gesture, symbolizes her freedom from the passions provoked by ill-controlled senses, allowing her to rise above worldy temptations and behaviour.

Late 15th – Early 16th Century

At the end of the middle ages, epic subjects became popular. Tapetries illustrated kings and princes in tournament, combat scenes and hunting parties. This period remains the most prolific for unrivalled masterpieces.

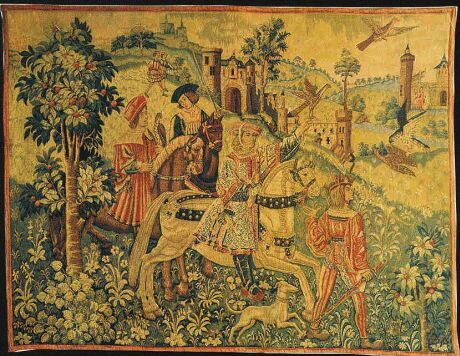

The tapestry Le Depart pour la Chasse, (above) aka “Plaisante Chasse” or “Chasse de Volerie”, depicts hawking, a favourite pass-time of the lords of the period. Thought to have been the cration of Flanderine workshops (C1500), this medieval masterpiece today adorns the vaulted rooms of the Cluny Museum in Paris.

A lord setting off on a hunt is distinguished by his highly decorated coat and his light coloured horse as he rides away from his chateau. His leather gaiters protect his calves from being scratched by the undergrowth.

16th Century

At the time of the Italian Wars, and with the Renaissance and the arrival of Italian artists, tapestry radically changed style.

Rich borders and arabesques characterised the highly coloured style of the Renaissance period.

The tapestry Promenade Medieval (above left) is of the style that links between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and reflects the manner of life of the period. The tapestry is a masterpiece of high quality weaving of the 16th Century.

After the Italian Wars, the Renaissance radically changed the art of tapestry making. The new aesthetic form was an association of painting and tapestry. Around 1530, Francis I founded the first Royal tapestry workshop at Fontainbleau in France. The great Italian artist, Le Primatice was the chief painter and decorator.

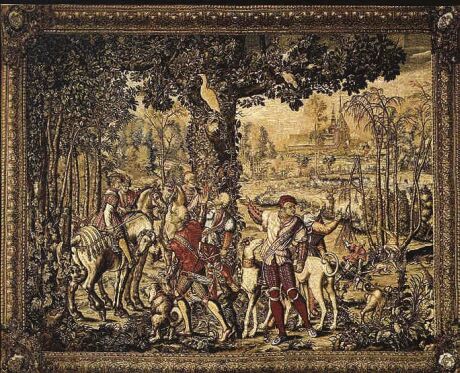

The tapestry Retour de Chasse (above right) depicts a lord, accompanied by his beaters, is returning to his property seen in the distance. The tapestry holds all that characterizes Renaissance art: composition, decor, perspective, light and borders of fruits, flowers and birds. The richness and elegance of the costumes in this Renaissance masterpiece contrasts with the austerity of medieval tapestries.

16th Century

Weaving Technique – The Raphael Cartoons

Associating painting with tapestry Raphael introduced the art of composition, order, clarity, perspective and light. Raphael’s work translated into a series of ten very famous tapestries known as the Acts of the Apostles, for the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Rome. The primary purpose of the paintings produced by Raphael was to be used as templates (or blueprints) by weavers for producing the tapestries and these paintings are known as “cartoons”. The Raphael cartoons have become as famous as the tapestries themselves. Raphael was commissioned in 1515 by the Medici Pope Leo X (1513-21) to produce the works and are the oldest surviving cartoons on paper.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes – the Raphael cartoon depicted above left and the woven tapestry produced from the cartoon shown above right.

In 1517 Raphael’s cartoons were sent to Brussles for weaving in the workshops of Peter Van Aelst and were finished around 1521. The tapestries were woven on a low-warp loom (or basse-lisse technique) whereby the cartoons were cut into strips by the weavers and placed beneath the warp (vertical) threads of the loom, following the design with the coloured threads of the weft (left to right). The width of the strips was limited by both the size of the loom and by the arm-span of the weavers working side by side, with their cartoon strip placed next to their colleagues.

The weavers worked on the back of the tapestry, producing a mirror image of the cartoon, which therefore had to be designed in reverse.

Many of the cartoons by celebrated artists were later re-joined and have become valuable artifacts in their own right.

17th Century

Around 1660, Colbert founded the Royal Factory at Gobelins, under the name Royal Workshop of Crown Furniture and later renamed to Beauvais in 1664, under the protection of Louis XIV. By 1675, more than 800 painters and tapestry makers could be seen at the Gobelins in Paris, under the brilliant direction of Charles Le Brun, whose idea was to group artists according to various talents.

Le Brun had each artist specialize in that for which he had an affinity and gift. This is why it is not unusual to find cartoons signed by several artists. In the 17th century, the perfection of the tapestry weavers had reached it’s pinnacle, the stitch had reached a maturity never before attained.

The inventory of the King’s furniture at the death of Louis XIV, contained no less than 2155 Gobelins tapestries woven under the auspicious direction of Charles Le Brun.

The tapestry La Chasse au Cerf, le Rapport, (depicted above) is one of several tapestries from several series of tapestries produced over two centuries known as the Maximilien tapestries after the emperor Maximilien. The model shown above was woven in the Gobelins and hangs in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Mid – Late 17th Century

This was a period where the “Verdures” – themes featuring greenery and foliage rose to popularity.

The tapestry Verdure de Flandres (above), was woven in Brussels and hangs in the Museum of Art and Decoration in Paris. This work is of outstanding quality, both by it’s perspective and the luxuriance of it’s foliage.

18th Century

After the death of Louis XIV, (1638-1715), the formal subjects gave way to more imaginative compositions. Tapestry weaving became more romantic with beautiful landscapes: this style reaching its peak with Boucher and endured during the entire reign of Louis XV. During this time tapestries depicted sensuality, provocative nudes, voluptuousness – all set in charming landscapes, where fallen gods and erotic nymphs dance.

Leda and the Swan (above left) and Sacrifice to Cybele (above right) are two tapestry that illustrate the sensualness of 18th Century tapestries. Sacrifice to Cybele is reproduced from a painting by Jaan Breughal, depicting nymphs and peasants making offerings of fruit, flowers and crops as gestures of thanksgiving to Cybele, the godess of nature.

Mid – Late 18th Century

Tapestry techniques became greatly modified, the compositions more mannered and the themes more stylish and elegant. The leading painters of the day continued to compose tapestries as if they were paintings and gone was the practicality of useful function as in the middle ages. Tapestries were now strictly for aesthetic and decorative values.

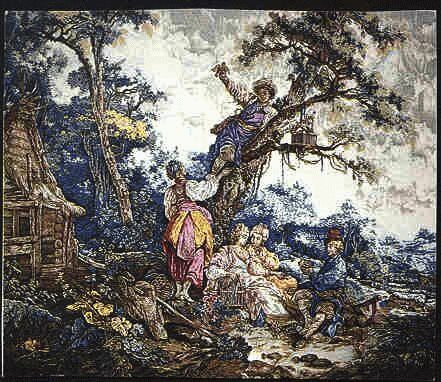

J.B. Leprince a student of Boucher, was one of the most well known painters at the start of the 18th Century. He created a new kind of exoticism based on the Northern Countries. With the Russian Games, six works at the Musee de L’ancien Archeveche in Aix-en-Provence, he introduced for the first time to French decoration the people, costumes and picturesque aspects of Russian life.

The tapestry above Les Marchands d’Oiseaux is typically 18th Century by its spirit, grace and easy rendering of the ambient northern light. This tapestry was executed in Beauvais in 1770.

The Jacquard Loom

In 1757 Jacques de Vaucanson developed a low warp (basse-lisse) loom that was improved by Joseph Maree Jacquard (1752-1834). This loom was to be the pre-curser of the technique used in the jacquard looms of today, and increased the speed at which tapestries could be reproduced.

Weft yarns (left to right) of different colours are woven from the back of the fabric to the face of the tapestry to form the design, the purpose of which was to imitate hand woven tapestry. Today, many forms of jacquard weaves of varying qualities are incorporated into the manufacture of jacquard tapestries. Different makes of Jacquard loom impart their own “fingerprint” or look to the tapestry they produce and these tapestries usually derive their name from the place (or workshop) of manufacture eg. Halluin, Gobelin, Louvieres and Loiselles.

The French Revolution 1789-1795

At the end of the French Revolution, artistic inspiration was abandoned. The Royal Workshops became government institutions managed by civil servants and the group of foreign artists painfully assembled under Charles Le Brun was broken-up.

Vandalism, pillaging and destruction reigned everywhere with some of the most beautiful tapestries burned in order to extract the small amount of gold and silver thread used in their weaving. Others were used as wind-breaks for vineyards or shelter for street peasants and refugees. The First Empire and reign of Napoleon I brought the final downfall of the art of tapestry and no masterpiece was to emerge from this confused era.

Beauvais, Aubsusson and Fellitin re-opened in 1795 and specialized in upholstering chairs. They limited themselves by reproducing tapestries from the old designs of the great artists of the 17th & 18th Centuries, reproducing tapestries in their thousands until the 19th Century.

19th – 21st Centuries

Tapestry design and manufacture have once again become the subject of popular decorative taste and many styles have emerged during this era.

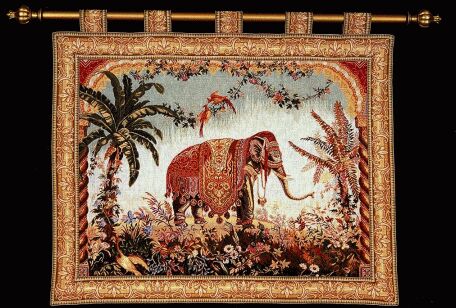

The Elephant tapestry, (above) although first appearing in the mid 19th Century, finds popularity at the close of the 20th Century. This tapestry is reproduced from a portion of a large tapestry that hangs in the Louvre, Paris. The original was woven in Aubusson in the middle of the 19th Century, a period where “Orientalism” was the trend.

Today “popular” tapestries are jacquard machine woven by boutique weavers in France, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Egypt and the USA and Aubusson hand woven tapestries being woven in China. Once again tapestries are produced for their aesthetic and decorative values, in varying themes and artistic styles that are inspired from film, television, home fashion and decorating.